Romania

These photographs were made during three trips to Romania, which together consisted of driving more than 10,000 kilometers, photographing much of the countryside and many of the cities. Romania is an important country with a vital culture on the brink of great change. Last year Romania was invited to join NATO and in 2007 she is scheduled to become a part of the European Union: two major developments for a country that has endured most of the Twentieth Century behind the Iron Curtain.

The picture of contemporary Romania consists of complex ironies that have come to define the character of its people. When Romania allied itself with Russia during World War II it adopted an idealized communism that quickly blackened and rearranged the country’s identity. With the longest harvest season of any other country in Europe (7 months) Romania should have remained a formidable agricultural economy. The ambitions of the communist leaders from the middle of the 1940s to 1989 have been strongly oriented to industrialism. Refineries, chemical plants and aluminum factories pepper the perimeters of cities where tens of thousands of people were relocated from the farms that their families had lived on for centuries. Forced to adopt the new industry, many families were severed from the history and tradition that nourished the spirit of their society. In the process they became cogs in the machine of the neo-Stalinist philosophy. It is arguable that as many as five generations are identified by the struggle to survive under the failing system of Romanian Communism.

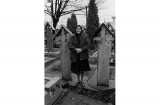

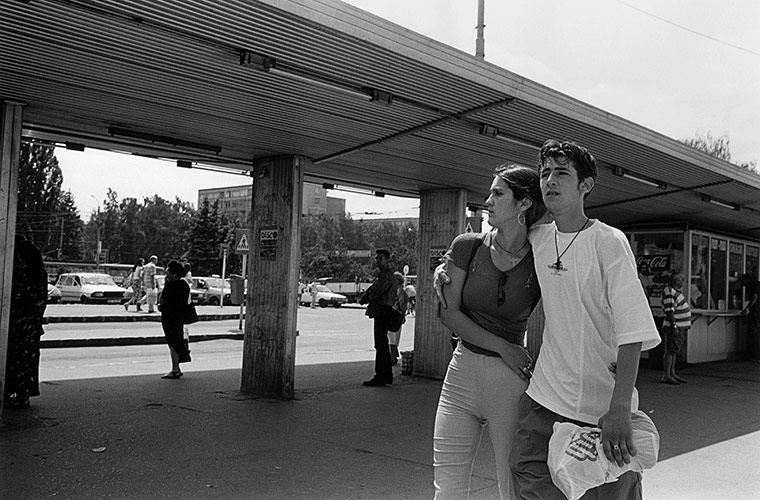

Today in Romania the signs of Western capitalism are rampant. Despite this and the industrial infrastructure surrounding the cities, Romania is otherwise provincial and traditional in appearance. When one travels the countryside of Romania it is easy to imagine that things did not look much different in medieval times. The farmers, marginalized by the industrialist plan, still sow and reap by hand with handmade tools. Plowing and gathering is done by hand, and transportation to and from markets is by horse drawn wagon. The rolling hills are roamed by shepherds and their sheep. There are very few exceptions to this. It has been this way for hundreds of years. The people’s religious and cultural traditions are also remarkably intact. Particularly in the areas of the country most geographically isolated from the capital, Bucharest, one can find tradition’s steadfast presence in daily life. Like other places where there have been protracted limitations on the populace’s freedom, the human consequence of repression has had the ironic effect of preserving traditions that would likely have been replaced by new world, international trends.

The real story of my journey to Romania is a very personal one that has analogies of general importance. I traveled there with a friend who was born and raised in Bucharest. His family lived on a farm located on the outskirts of the city where they made a simple life for themselves: living in autonomous peace and modest comfort. They worked proud but menial jobs for the State in health and statistics. In the 1960s, Nicolae Ceaucescu, demonstrating the first signs of his paranoid megalomania, decided that villages, farms and communities jeopardized the health of the Communist future by fostering environments for mini-societies. In an effort to nip this perceived problem in the bud, he razed many dozens of villages in the country and plowed under hundreds of farms, thereby forcing entire communities to relocate to the State-built dormitories that would by the 1970s ring the perimeters of most of Romania’s cities. People were forced to work in factories, en masse, in an attempt by the government to energize its new industrial economy.

In a small dirt parking lot within one of these housing complexes that looks identical to so many other small dirt parking lots all over Romania, there is a bent, knotted apple tree growing from the fallow dirt. As we stood before it, my friend explained that this was the tree that he spent much of his childhood climbing. It was in his backyard before his house was destroyed and the new buildings were erected. His family was relocated to one of the cement dormitories across the street where they remain to this day. The survival of this tree is significant as it represents the bits and pieces of the past that grow through the cracks of Ceaucescu’s plan: it is these persevering elements of the past that will, at least metaphorically, be the strength upon which the Romanian people will need to draw in order to rebuild their spirit for the now blossoming future.

—Peter Kayafas (2005)

Press

BLOG: Oitzarisme, Romanian culture blog featuring Peter’s photographs.