The Merry Cemetery of Sapanta

Sapanta is a small village situated in the northern part of Romania in the region known as Maramures. The 3,500 inhabitants of Sapanta are, like the people of Maramures in general, recognized for their strong character and their ability to combine the traditions of the past with the modernity of the present—this is the key to understanding the phenomenon of their village cemetery. The Merry Cemetery, as it has come to be known, is unique both in Maramures and in Romania.

I visited the Merry Cemetery of Sapanta and met its creator, Stan Ion Patras (1908–1977), in 1962. Patras’ fame was well established by then and he had a steady flow of visitors. As he would put it in the long autobiographical epitaph he composed for himself (and of which only a small part could fit on his cross): “With lots of people did I sit talking/ Over twenty thousand/ All liked me/ I received them well.”

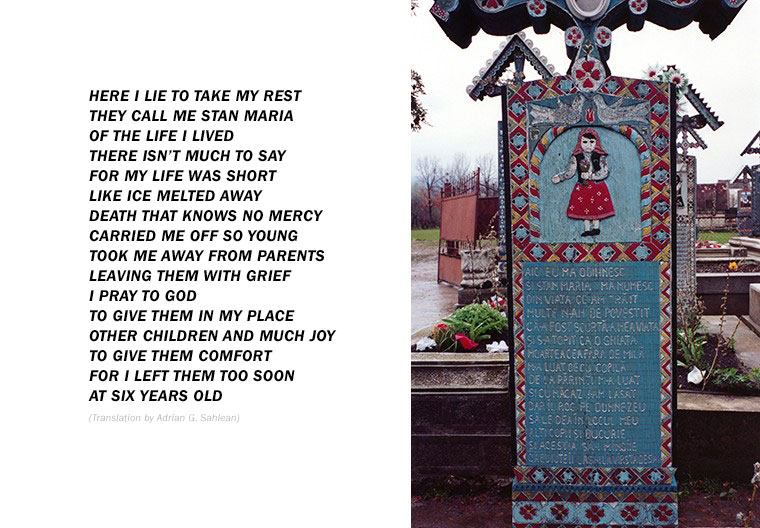

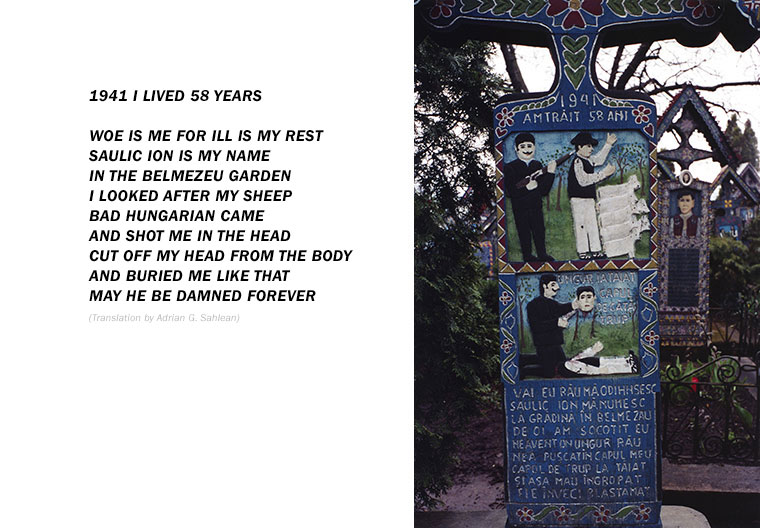

In the mid-1930’s Patras made a living carving the ubiquitous monumental wooden gates that Maramures farmers take pride in as well as crosses for the cemetery in his village. Little by little, wishing to better serve his clients, he started to paint the crosses in order to protect them from rain and frost, thus making them last longer. Blue was the color that imposed itself from the very beginning. Gradually, the geometric and floral motifs, as well as those of the sun and moon that he had carved on the gates, were incorporated by Patras into the crosses. The colors he chose for these motifs were those he saw around him: on the woven rugs and clothes for which the Sapanta women were reputed, on the local ceramic, or on the icons painted on glass. Thus, the blue background came to alternate with red, yellow, dark green, black and white shapes.

Patras could not have invented the “merry” cemetery that he wanted had he not been deeply immersed in the local traditions. His conversations with the villagers who ordered their crosses and told him how they were to look, appear to have been extremely important for the gradual elaboration of Patras’ understanding of what the Sapanta cemetery should look like. The carved and painted inscriptions continue these dialogues, hinting at things that must have been told to him on the occasion.

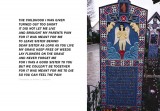

Systematic use of the first person singular and the present tense in most inscriptions gave to the voice of the deceased an existence that seemed to continue, interrupted but not stopped by death. From case to case, specific, personal anecdote enriched these texts. Some of their “utterers” had had special professions, which deserved to be mentioned. Others had worked with passion, loving their cattle, horses, apple-trees, grassland or house with an intensity that set them apart. For some, the specificity of their epitaph derived from the circumstances of a prolonged illness, an unexpected early death, or an accident. Others had died far from Sapanta, at war, in political prison, while mining and, nowadays, in the richer European countries where they temporarily migrate in order to make ends meet.

The effect of the perpetually renewing work of Patras is strong. The village of the dead is loquacious, its dwellers talk with the ease and humor of the living Sapanta people. Each of them would like to be visited and invites you to recognize or to discover her/him.

The villagers answered the unfolding idea of Patras with so much enthusiasm that he had to hire help and find apprentices. The number of crosses to carve and paint grew steadily. To this one should add the upkeep work. Crosses had to be repainted, or at least refreshed, after eight or ten years. Since men often work with wood in Sapanta, when they don’t raise cattle, it was not difficult to find whom to teach. As long as he lived, Stan Ion Patras carved and painted, and was ultimately followed by his apprentices Gheorghe Stan, Toader Stan, Toader Turda (who was his nephew) and Vasile Stan (nicknamed Coltsun).

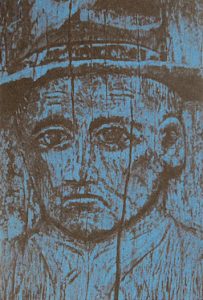

It is difficult to imagine at what moment Patras decided to paint a portrait of the deceased on the upper part of the cross. What seems clear, however, is that the idea must have originated not only from the painted troitsas (crosses erected on the roads, usually representing Jesus Christ or the Mother of the Lord) but, at least in part, from the newer custom of putting photographs on the crosses in rural as well as urban cemeteries. It is possible that Patras tried to paint portraits that do not easily deteriorate, as photographs do. Maybe he wanted to help, knowing well that his fellow villagers could not afford to pay for the more expensive glass or porcelain photographs of which they were fond. And we shouldn’t exclude the simple joy he must have felt when realizing that he was able to do something that had never been done before.

So, the crosses in Sapanta came to include painted representations of those buried underneath. The blue village of the dead, with its cross-houses, gained overnight, due to Stan Ion Patras, the windows through which one could take a glimpse of the personalities of those who had come to dwell in it.

— SANDA GOLOPENTIA, Brown University

The Merry Cemetery

A film by John Giura by Peter Kayafas

Press

REVIEW: “Grave Matters,” The Boston Phoenix review by Christopher Millis of Peter’s exhibition and book The Merry Cemetery of Sapanta, July 15, 2008.